Multiple Perspectives of “The Problem”

Modern organizations are complex, and the sorts of problems that remain to be resolved using process redesign, IT systems design, or the combination of both that we call the co-design of business & IT systems can’t be defined around a simple set of issues. There are multiple managers and groups of stakeholders, with competing goals for change. Some of these overlap, some complement each other, and some are in conflict with those of other stakeholders. Even a group of people who work together will have differing requirements and goals, depending on their experience, their professional background, and their position in the organization. People understand the parts of the organization they have experience of. Those who have worked in multiple groups will have a much wider – and more complex – view of what needs to change than those who have worked in the same role for years.

There’s a management consultancy joke that says if you get five stakeholders around a table, you’ll have at least fifteen different goals.

The co-design of business & IT systems is like piecing together a jigsaw puzzle without the picture. You get an edge here and there, part of a building outline, or a connecting feature, but mainly you are assembling bits and pieces that are tacked together in whatever way makes sense at the time. Most IT analysts fudge this by merging stakeholder requirements for change under a single, vague business goal. But this doesn’t prevent the shift in focus between multiple objectives that stakeholders prioritize, as these become salient to the current area of design. Change analysts have to understand multiple business domains, as stakeholders’ requirements indicate different types of solution and the analyst attempts to integrate these around a coherent business vision. Even business managers don’t really understand their processes – and know very little of the processes with which their area of responsibility interfaces. Conflicts, priorities, and omissions in change objectives are seldom realized as the logical analysis methods used for IT requirements don’t provide ways to map out the full scope of change – the big picture.

We lack ways to represent the big picture of how the organization “works” in ways that would allow business managers to understand the implications of changing things. Business analysts, change managers, and IT systems analysts are in a no-win situation. They are expected to understand myriad interpretations of the business strategy, reconcile conflicting viewpoints on how business processes work, and somehow define a coherent set of change objectives that pleases everyone. All while business managers and stakeholders each understand only a fraction of what the business does.

Goal-based design is a myth

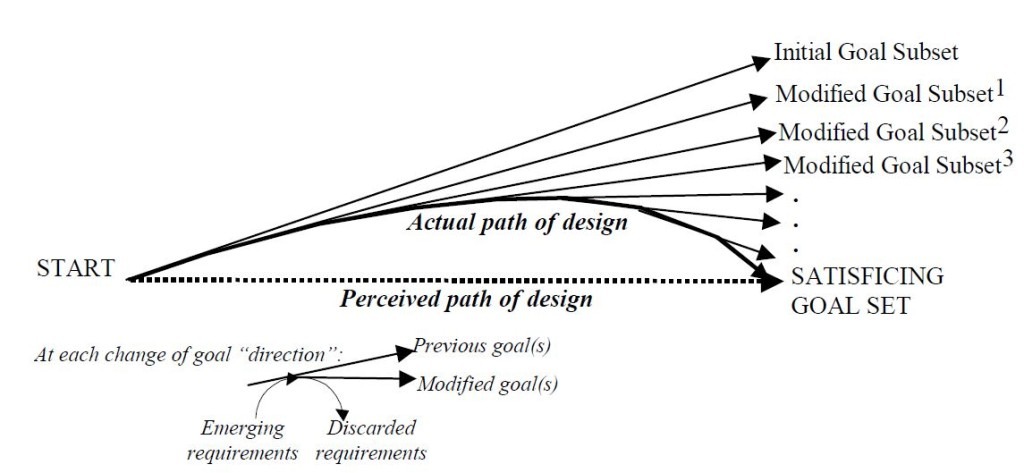

In today’s complex organizations, very few design goals are understood to the point that they can just be stated and agreed across stakeholders. Design-goals are constantly changing between iterations, as shown in Figure 1. The designer starts by designing for the subset of goals they understand. As they explore and test the design with users, they become aware of new requirements and so modify the subset of goals they are designing for. As part of this process, they also discard any requirements that are no longer associated with perceived user needs.

Organizational change requires repeated cycles of appreciation, enculturation, inquiry, learning, change, and evaluation – until the design is good enough. Not perfect – and certainly not optimal – good enough is good enough [2]. We talk about design as if it were fixed: as if there were one best way to design everything. We celebrate designers who produce especially elegant or usable artifacts as if they were possessed of supernatural powers. Yet design should be easy. It is the application of “best practice” principles to a specific situation. We can observe how the users of a designed artifact or system work, then design the artifact or system accordingly.

Why does that approach fail so often? Because designers fail to design for changes to business processes.

The co-design of complex organizational processes & IT systems

We cannot implement changes to IT systems without changing the way in which people work, how work is organized, and what it achieves. Most often, achieving improved business goals is the whole reason for IT change, as business environments and competitors change – and our business strategy needs to change to match this (or anticipate it).

The drivers of change are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Drivers of IT ChangeBecause IT change is always accompanied by changes to how people work, we need to design IT systems to support the changes we want, rather than work against them. For example, if we want people to collaborate, designing a system that prevents people from sharing information is a non-starter. So we need analysis methods that models the various systems of work-activity, understands the complex purposes of these systems, and defines requirements for the IT system to achieve these purposes. As shown in Figure 2, IS applications support business processes – they do not define them. Too often, IT design is performed in isolation, by technical developers who do not understand how the business works.

Figure 3 presents a revision of Leavitt’s diamond model (Leavitt, 1960), updated for the 2020s. The original model related four aspects of the organization – structure, technology, task, and people – in a diamond model that communicated how changing any of these factors impacted the others. In 1991, Michael Scott Morton updated the model, to place managerial processes at the center, redefining the four “diamond model” factors as structure, strategy, technology, and individuals & roles. Scott Morton also related the organization to the external technological and socioeconomic environment.

The updated model presented here is my version of this framework. It presents the organization as situated within its environments – business/competitive, global, socioeconomic, and technological – rather than separate from these. Organizations are much more complex than in the 1990s. They incorporate multiple structures and power-centers/roles (management), business strategy cannot be separated from business intelligence, IT is integrated with data management and analytics, and people are identified with the work-activities they perform and the knowledge that they bring to their work. These four aspects of business organization are organized around the flows of high-level business processes that are performed to achieved each of the multiple purposes that the business exists to achieve.

References

Leavitt, H. J. (1964). Managerial psychology: An introduction to individuals, pairs and groups in organizations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Scott Morton, M. (1991) The Corporation of the 1990s: Information Technology and Organizational Transformation, Oxford University Press.