Step 3: Define Root Definitions of Relevant Systems

This stage of the analysis clarifies what the system of human-activity exists to achieve by defining Root Definitions. These definitions separate and clarify different purposes of the system (or mess) of human-activity, allowing you to define what needs to be done by using a “divide-and-conquer” approach.

Checkland argues that until you have put a name to something, you cannot possibly understand its function or purpose. The Root Definition “names” the system in a structured way. Various subsets of work-routines perform similar activities but for different purposes, with different success criteria and outcomes. Root definitions start with the “purposeful system” transformations from stage 2, then clarify these alternate perspectives on work-system purpose, defining exactly what each activity subsystem needs to accomplish.

A Root Definition names the system which supports each transformation.

The important thing is to examine each transformation from one perspective: you can happily repeat the exercise using another perspective, to see if you can integrate the two (sometimes this may not be possible, for example, how do you integrate the needs of drivers in transformation (1) with the needs of pedestrians?). If you cannot integrate competing perspectives, you must take a decision about whose perspective will have priority — this is where your client’s objectives come into play. In every change, there are winners and losers; your job is to make it explicit who loses and who wins to your client – not to make the decision for them.

Use the CATWOE framework to produce a Root Definition for each transformation defined in Step 2:

| Customer: | Who is the system operated for? Who is the victim or beneficiary of this transformation-system? |

| Actor(s): | Who will perform the activities involved in the transformation process? It is important to define a set of people acting in concert. If you have multiple sets of people, this normally indicates that you are confusing two or more transformations. |

| Transformation: | What single process will convert the input into the output? It is important to define a single (not complex) transformation. If you have multiple verbs, this normally indicates that you are confusing two or more transformations. |

| Weltanschhaung aka Worldview: | What is the view which makes the transformation worthwhile? Understanding this element communicates the real purpose of the system from this perspective, so you should work hard at this part. |

| Owner: | Who has the power to say whether the system will be implemented or not? (Who has the authority to make changes happen?) |

| Environment: | What are the constraints (restrictions) which may prevent the system from operating? What needs to be known about the conditions that the system operates under? |

The most important part of the CATWOE is the Weltanschhaung (German term for a particular philosophy or view of life; the worldview of an individual or group). You can just phrase this as “Worldview” if it makes life easier. The Worldview attached to a transformation communicates why it is important to the actors involved to achieve this purpose of the system of work. So we need to explore this in conversations with those involved and work hard at surfacing their rationale for the transformation.

Minimalist Root Definitions

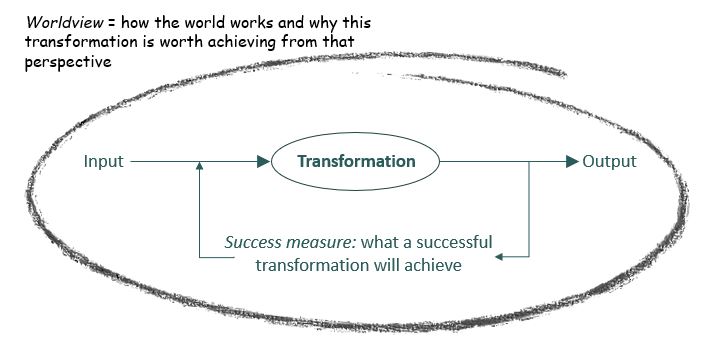

When working with business people, it may be difficult (and tedious) for them to define the CATWOE elements for each transformation. In these situations, I use a minimalist root definition, as shown in Figure 3-1. I start with the Worldview: why is this transformation important to achieve the purpose you are aiming for. Then I focus on evaluation of the outcomes: what regulates the process (i.e. what causes you to adjust how you achieve the transformation), and how do you measure success (how do you know if you achieved your purpose)?

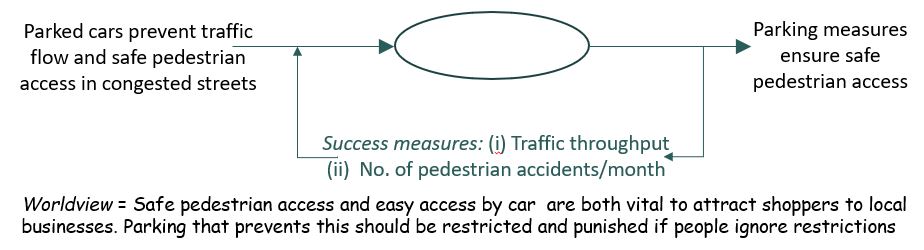

When deriving Root Definitions, the actual transformation can be elusive. You often need to iterate, redefining inputs and outputs, then trying to surface the context of the definition from the input-output combination that you have defined. For example defining the transformation in terms of “running a parking system” is meaningless. It tells us nothing about what the process is which gets us from cars parked in inappropriate places to cars parked in appropriate places. Similarly, defining the input-output as “illegally-parked cars” and “legally-parked cars” tells us nothing about how illegal and legal will be interpreted by different people involved in the system. You need to either define illegal in your Worldview (e.g. Worldview: “Parking in congested streets causes accidents, so it should be punished by law”) or define the input and output more clearly (i.e. Input = cars parked in congested streets; Output = no cars parked in congested streets). By being precise about terms, everyone involved in the system understands exactly what is involved, what activities need to take place, and how the system’s success can be measured, as shown in the example given in Figure 3-2. Note that the name of the transformation is not yet defined – this should follow from the analysis, rather than constraining what we consider as within scope for this purpose.

If we just said Worldview: “Parking should be punished by law”, this does not communicate the perspective of how important it is that this should happen, or why it should happen. However, Worldview: “Parking in congested streets causes accidents, so it should be punished by law” communicates two things – the rationale for prevention of parking (unblocking congested streets) and the reason that the stakeholder wants this as a purpose of the system (to reduce accidents).

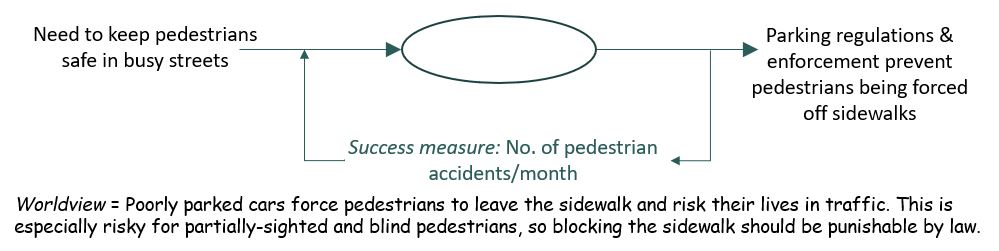

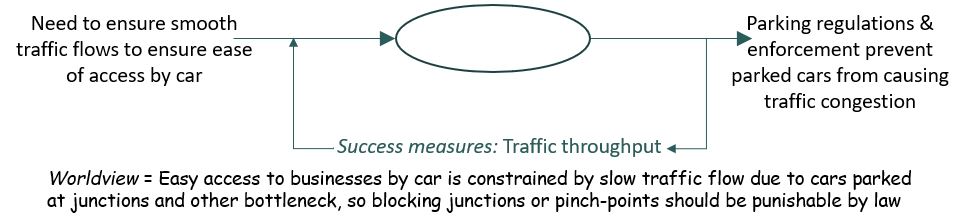

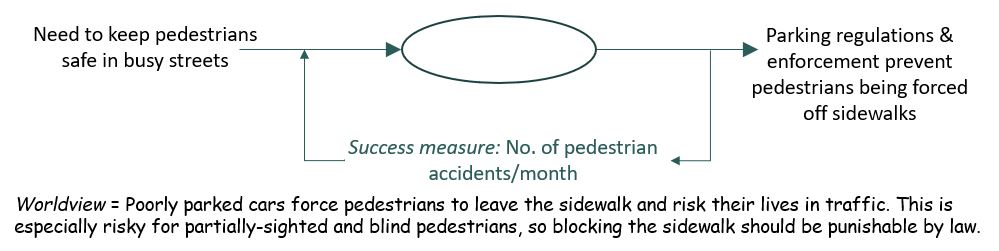

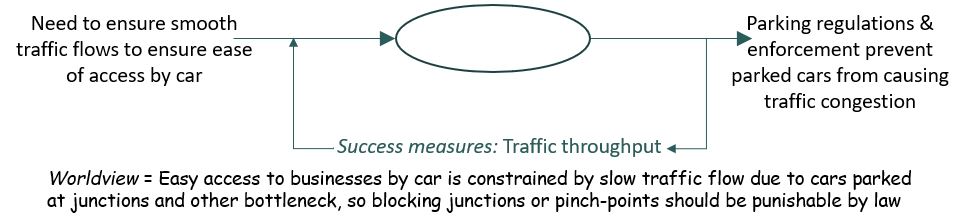

However, the example in Figure 3-2 still conflates two separate purposes: to keep pedestrians safe and to maximize traffic throughput (making access by car easier). These need to be split into two separate transformations. The result is the two transformations shown in Figures 3-3 and 3-4.

The transformations are analyzed iteratively, in collaboration with actors and stakeholders involved in the problem-situation, to refine and separate purposes until stakeholders feel that these describe the logic and all aspects of the “root purpose” of the system, from a single perspective. They are then written out as Root Definitions, to formalize everyone’s understanding of each purpose. If possible, stakeholders are encouraged to provide details for the rest of the CATWOE framework at this point, as it is needed for the Root Definitions. If this is not feasible, I usually extrapolate from known information, to fill in the blanks!

Formalizing Root Definitions

At this point, the Root Definition can be written out, so that everyone understands exactly why we need the system from this perspective, and what transformation is needed to fulfill the system purpose. For example, the transformation shown in Figure 3-3 (repeated here for clarity) could be expressed as follows:

Root Definition 3-4: A system owned by City Government traffic management division, which polices and penalizes parking that puts pedestrians at risk, because pedestrian safety should have priority over driver convenience and drivers will not consider safety a priority unless they fear punishment. The system will operate under the constraints of powerful drivers’ political lobby groups, who consider unlimited road-use a right, the need for a self-financing system of parking enforcement, and the culture of City Government that ascribes a low priority to pedestrian safety.

Note that the Worldview expressed in the original transformation of Figure 2-4 has been elaborated and developed substantially during the process of formalizing its definition in this way. The addition of the need for drivers to “fear punishment” in order to take pedestrian safety seriously, and the constraints of financing and the local Government culture, both add to our understanding of what needs to be done as part of the system of work that will achieve this purpose!

Similarly, the transformation shown in Figure 3-4 (repeated here for clarity) could be expressed as follows:

Root Definition 3-4: A system owned by City Government traffic management division, which polices and penalizes parking in traffic junctions and other bottleneck points, because local businesses require high traffic throughput to be successful and drivers often cause major road congestion that can tail back for several miles by parking at these points. The system will operate under the constraints of limited parking space availability (which requires parking time limits), the need for a self-financing system of parking enforcement, and the need to provide additional longer-term, off-road parking for local business employees.

Once the root definitions have been defined, it is time to explore how these translate into conceptual models, showing the activities needed to achieve the transformation.