Systems Thinking

Typically, systems requirements analysis fails because of two reasons:

- The analysis is not sufficiently systemic – it reduces a complex system down to a subset of activities and work-goals that can be understood.

- The analysis is too focused on what can be computerized. It does not analyze what needs to change, but what the IT system should do to support an [implicit] set of changes.

Why are systems changes counter-intuitive?

The human mind is not adapted to understand the consequences of a complex mental model of how things work. There are internal contradictions between future structures and future consequences, that become difficult to balance when multiple mental models are involved. Most people are “point thinkers” who only see part of the big picture. It is easy to misjudge the effects of change, when you only base your arguments on a subset of cause and effect. Systemic thinkers analyze interactions between various factors affecting a situation, to understand cycles of influence that affect our ability to intervene in changing the situation.

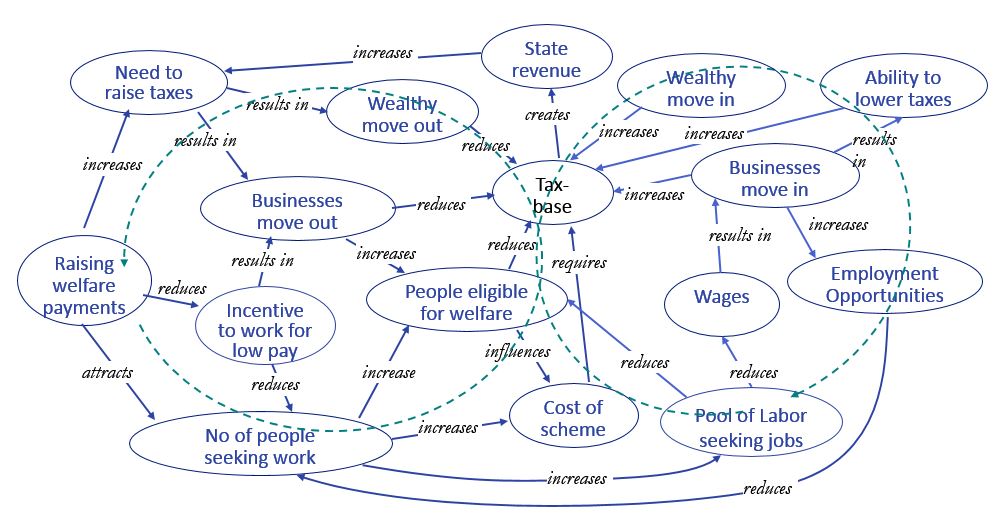

An example of counter-intuitive set of influences is shown in the “systemic” view of a limited social welfare system, given in Figure 1.

We have two opposing “vicious cycles” of influence, in this model:

- The left-hand cycle reinforces the argument that raising welfare payments encourages “entitlement” and disincentivizes work.

- The right-hand cycle supports a counter argument, that raising welfare payments attracts job-seekers and increases employment, raising tax base revenue, to provide a net benefit (as well as humane assistance).

Unless a complete view of the whole system of interrelated processes is obtained, well-intentioned changes have unintended consequences. It is necessary to understand the system as a whole, rather than individual effects between factors, to understand these “vicious circles” of cause-and-effect. Tweaking one element will affect others, with knock-on effects as the two cycles interact. The only way to ensure a specific outcome is to intervene to break the cycle of influence (change the relationship between factors), or appreciate the interaction effects, so you can predict the outcome.

In the pages that follow, I explore Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) – an approach that provides a philosophy and a set of techniques for investigating an unstructured problem situation without the constraints and blinkers that come with systems requirements techniques. SSM investigates an organization as a system of work-activities that may or may not require computer-based system support in solving problems with this system of work. Most methods for Information Systems requirements determination place the investigator (the systems analyst) in the role of “expert”. In other words, the analyst attempts to understand the organizational situation, determines what computer system functions are required by interviewing potential system users and/or managers, then draws on their expert knowledge of other computer systems to specify a hardware and software “system”, based upon their understanding of the organizational situation and tasks. If the analyst’s understanding is incorrect or incomplete, this is usually not detected until the system is tested by its organizational users, which may not happen until the system has been installed. This situation occurs because system users do not normally possess sufficient technical knowledge to understand and question the highly-technical system specification documents which the analyst produces, so any misunderstandings are not revealed until the system is built. One way of avoiding this problem is to produce a system prototype, where the system designer builds a trial version of the system for the users to try out. Comments and criticisms are fed back to the designer, who changes the system and produces another prototype; this process is repeated until both designer and users are happy with the system’s operation. However, prototyping is not appropriate for all development situations (such as very large, complex systems, where each user will only understand a very small part of the system’s operations) and also, a great deal of effort in producing and modifying inappropriate prototype systems can be avoided if a more effective investigation is performed into the system requirements in the first place.

The advantage of SSM in such cases is that it models explicitly the different value-systems (perspectives) of various people in the organization, representing different people’s differing beliefs about the effectiveness and purpose of the organization (or their part of the organization) and their perceptions of current information systems within it. When organizational problems are difficult to define, many problems can be due to work “systems” (for example a department) prioritizing one set of organizational objectives at the expense of another set of objectives. For example, a computer-based system for the authorization of traveling expenses, used by staff in the accounts department may have been designed to reject claims which do not conform to low-cost criteria. Use of this system will force (or “encourage”) staff to use the form of travel which has the lowest cost (e.g. train rather than car) even when the company may lose business by someone not being able to reach a business client before a competitor. The use of SSM for the analysis of requirements for a traveling expenses system would make this conflict explicit, leading to the specification of an alternative system which was able to flexibly approve the expense on the joint criteria of cost and urgency.