Appreciating The Context of Organizational Activity

Human-centered design requires that we understand – or rather, appreciate – the need for changes to a “real-world” situation that is viewed as a governed by business logic and goals – rather than the engineering logic employed for IT system requirements. The intention is to improve how we understand the need for change – and the systemic impacts of making changes – through an iterative learning process based on Vickers’ concept of Appreciative Systems (Vickers, 1968; Checkland, 2000b).

Geoffrey Vickers observed the diversity of norms, relationships, and experiential perspectives among those involved in, or affected by, a system of human-activity such as that found in business work-organizations. He argued that organizational change analysts needed methods for analysis that explored how to reconcile these perspectives, developing the concept of an “appreciative system,” the set of iterative interactions by which members of an organization explore, interpret, and make collective sense of their shared organizational reality (Vickers, 1968).

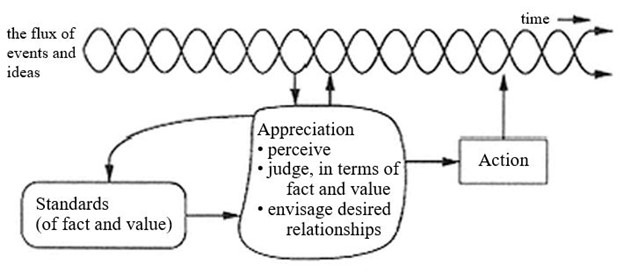

Vickers conceptualized organizational work as a stream, or flux, or events and ideas that were interpreted by participants in the organization by means of local “standards,” reflecting shared interpretation schema and sociocultural values (Checkland and Casar, 1986). Interpretations of new events and ideas are subject to the experiential learning that resulted from prior encounters with similar phenomena; these will vary across stakeholders, depending on how they interpret the purpose of the system of work-activity. To achieve substantive change, we need to understand and reconcile these multiple purposes, integrating requirements for change across the multiple system perspectives espoused by various stakeholders. These are separated out into distinct perspectives, which model subsets of activity that are related to a specific purpose or group of participants in the problem situation (Checkland, 1979, 2000b).

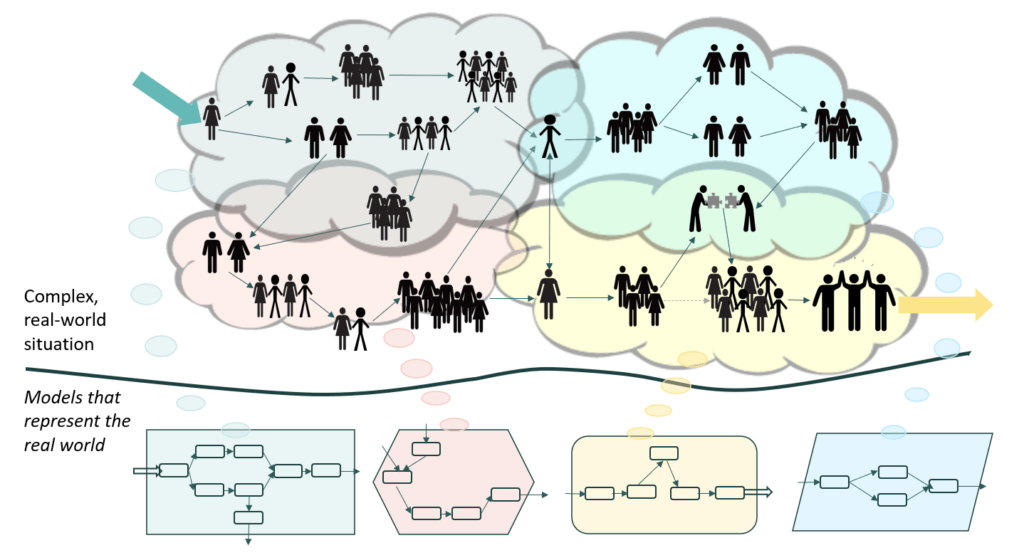

While both real-world analysis and systems thinking about the real world aim to produce representations of complex situations, the key difference lies in their focus: real-world analysis primarily examines data from actual scenarios to identify patterns of human-activity, relationships between actors, and issues that affect performance, whereas systems thinking takes a broader view by considering the interconnectedness of elements within a system, analyzing how they interact and influence each other to understand the big picture – and to engage in debate about how it may be improved.

The concept of appreciative design underpins Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), an approach devised by Dr. Peter Checkland of Lancaster University in the UK, to capture and make sense of complex change requirements across multiple goals for change and the multiple rationales that underpin any organizational system of work-activity. SSM is now a highly-regarded approach to managing complex change, especially suited to the untangling of “wicked problems” (Rittel, 1972). Its contribution is to separate the analysis of “soft systems” of human-activity – what people do in their work and the logic that makes sense of that activity – from the “hard system” of IT and engineering logic that usually underpins system requirements.

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM)

The development of integrative system thinking methods and analysis techniques to solve ill-structured, “soft” problems is Checkland’s (1979) contribution to the fields of change management and systems analysis. Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) provides a method for participatory design centered on human-centered information systems. The analysis tools suggested by the method — which is really a family of methods, rather than a single method in the sense of modeling techniques — permit change-analysts, consultants and researchers to surface and negotiate feasible aspects of change, to explore and reconcile alternative viewpoints, and to anticipate (to some extent) the knock-on effects of changing one part of a complex system of work on other parts of this system.

Problems are ultimately subjective: we select things to include and things to exclude from our problem analysis (the “system boundary”). But real-world problems are wicked problems, consisting of interrelated sub-problems that cannot be disentangled — and therefore cannot be defined objectively (Rittel, 1972). The best we can do is to define problems that are related to the various purposes that participants pursue, in performing their work. By solving one problem, we often make another problem worse, or complicate matters in some way. Systemic thinking attempts to understand the interrelatedness of problems and goals by separating them out.

In understanding different sets of activities and the problems pertaining to those activities as conceptually-separated models, we understand also the complexity of the whole “system” of work and the interrelatedness of things – at least, to some extent. It is important to understand that, given the evolving nature of organizational work, a great deal of the value of this approach lies in the collective learning achieved by involving actors in the situation in analyzing changes, and that this approach in inquiry is, in principle, never ending. It is best conducted with and by problem-situation participants (Checkland, 2000b).

Summary

To summarize, appreciative design is an approach where emergent perspectives on what a “system” of work should achieve and how that work should be performed are modeled to produce actionable changes to the system that can be evaluated around agreed standards of performance and that preserve desired relationships between human actors and between elements of work-activity and their outcomes. This approach to modeling work-systems influenced the development of Soft Systems Methodology (Checkland, 2000b), a method to operationalize the representation and negotiation of systems of purposeful human-activity around which desirable and feasible changes can be identified and implemented.

References

Checkland, P. (1979) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. Latest edition includes a 30-year retrospective. ISBN: 0-471-98606-2.

Checkland P., Casar A. (1986) Vickers’ concept of an appreciative system: A systemic account. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis 13: 3-17

Checkland, P. (2000a) New maps of knowledge. Some animadversions (friendly) on: science (reductionist), social science (hermeneutic), research (unmanageable) and universities (unmanaged). Systems Research and Behavioural Science, 17(S1), pages S59-S75. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/75502924/abstract

Checkland, P. (2000b). Soft systems methodology: a thirty year retrospective. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 17: S11-S58.

Checkland, P., Poulter, J. (2006) Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and its Use, for Practitioners, Teachers and Students. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-470-02554-9.

Rittel, H. W. J. (1972). Second Generation Design Methods. Design Methods Group 5th Anniversary Report: 5-10. DMG Occasional Paper 1. Reprinted in N. Cross (Ed.) 1984. Developments in Design Methodology, J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester: 317-327.: Reprinted in N. Cross (ed.), Developments in Design Methodology, J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 1984, pp. 317-327.

Vickers G. (1968) Value Systems and Social Process. Tavistock, London UK.