A Framework For Behavioral Studies of Social Cognition In Information Systems

Susan Gasson

Drexel University, USA

Please cite this paper as:

Gasson, S. (2004) ‘A Framework For Behavioral Studies of Social Cognition In Information Systems,’ Proceedings of ISOneWorld Conference, Las Vegas NV, 14-16 April 2004. Available from http://www.improvisingdesign.com/soc-cog/

Abstract

This paper examines framing processes in organizational information system definition, acquisition and use. Three theoretical lenses of social cognition are required to understand how individuals and groups frame IS problems and solutions. These are: (i) socially-situated cognition, (ii) socially-shared cognition, and (iii) distributed cognition. These three perspectives are often conflated in studies of that study mental models or framing in an IS context. The separation of analytical “levels” reveals different interiors of the “black box” of organizational IS design and adaptation, which are not well understood. In particular, this methodological framework highlights different assumptions concerning whether mental models are static or dynamic, and whether cognition is a property of individuals, groups, or technological systems.

Keywords: Social Cognition, Technological Frames, Mental Models, IS Design, Sensemaking, Improvisation

Introduction

The study of socially-situated cognition is becoming increasingly common in the information systems (IS) literature An interest in theoretical concepts such as organizational sensemaking (Weick, 2001), situated action (Lave and Wenger, 1991, Suchman, 1987, 1998), technological frames (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994), organizational improvisation (Orlikowski and Hofman, 1997, Weick, 1998), technology adaptation (Majchrzak et al., 2000, Orlikowski et al., 1995), emergent knowledge processes (Markus et al., 2002), and distributed cognition (Hutchins, 1991) reflect an attempt to understand the ways in which aspects of individual and group understanding inform the definition, design, acquisition, use and adaptation of technological systems that are situated within a specific social and organizational-work context. But much of this work is ad hoc and fragmented, with little understanding of the traditions that underlie these theoretical concepts and the relationship between them.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a structured discussion of different theoretical perspectives that are incorporated into situated (or contextual) analyses of social cognition. The situated perspective is privileged here because contextual studies of social cognition are emerging as an important development in the organizational and IS literatures (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994, Porac, 1996, Resnick, 1991, Winograd and Flores, 1986). In section 3, a methodological framework is suggested for studies of social cognition in IS, accompanied by a discussion of how these concepts may be operationalized. Finally, there is a discussion of how this framework may be applied in IS research studies.

Theoretical Perspectives on Framing

The study of the processes by which human beings individually and collectively interpret, bound and make sense of phenomena and social interactions in the external world originated in the fields of cognitive and social psychology. Human beings are thought to act according to internal, cognitive structures that represent or symbolize external reality, constituting a language of thought (Fodor, 1975). These structures are variously referred to as schemas (Bartlett, 1932, Neisser, 1976), personal constructs (Kelly, 1955), scripts (Schank and Abelson, 1977) or mental models (Gentner and Stevens, 1983, Johnson-Laird, 1983). Earlier notions of cognitive processing emphasized information processing over the construction of meaning; the importance of both context and meaning became de-emphasized as a result (Bruner, 1990). More recently, human cognition has been viewed as a process that is situated within a socio-cultural context (Porac, 1996, Suchman, 1987, 1993). Thus, meaning “derives from an interpretation that is rooted in a situation” (Winograd and Flores, 1986, page 111). Mental models become more complex, abstract and organized with experience: this is pertinent in the IS profession, where experiential knowledge is valued because it brings an increased capacity for abstraction (Vitalari and Dickson, 1983).

These cognitive structure concepts from the psychology literature converge, and are extended to organizational research, in the notion of a “frame” (Goffman, 1974, Tannen, 1993). Framing operates at the intersection of a psychological-cognitive and a social-behavioral approach to human interaction (Ensink and Sauer, 2003). In framing a problem-situation, an individual both structures and bounds those elements of the situation that they consider relevant, just as a film-director frames a scene.

Framing As Socially-Situated Cognition

Underlying any study of social interaction is the understanding that individuals inhabit a socially constructed world and through their actions, reproduce and give meaning to that world (Berger and Luckman, 1966, Kelly, 1955). Individuals operate within distinct “social worlds” (Strauss, 1978, 1983) or “communities of practice” (Brown and Duguid, 1991, Lave and Wenger, 1991): local workgroups possessing their own social norms, social expectations and specific genres of communication. But people are also members of multiple social worlds, as their work and personal experience intersects with the knowledge and interests of different groups (Strauss, 1983, Vickers, 1974). Thus, organizational problems and meanings are not consensual but emerge through interactions between the various social worlds to which decision-makers belong. People behave according to “structures of expectation” (Tannen, 1993) that guide how they predict and interpret the behavior of others. Such structures are partly culturally-predetermined and partly based on prior experience of similar situations (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995, Minsky, 1975, Schank and Abelson, 1977, Tannen, 1993).

Communications are framed both within a specific, situational context and from an individual perspective (Ensink and Sauer, 2003, Tannen, 1993). Individuals provide conversational cues, on the basis of which hearers are able to place the communication within a specific context. But an individual cannot contribute to a discourse without displaying their view on the subject matter. Thus, individual frames are not static, but subjected to change during communicative and social interaction (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995, Ensink and Sauer, 2003, Eysenck and Keane, 1990). Suchman (1987, 1998) demonstrates how shared definitions of technology and work spaces are produced and reproduced through interactions between technology, people and potential work-spaces. Managers and workers make sense of their organizational environment and innovate through improvisation, to determine what works in practice and how it may be changed (Middleton, 1998, Orlikowski and Hofman, 1997, Weick, 1998, Zack, 2000). Organizational processes may no longer be viewed as static, but as “emergent knowledge processes” (Markus et al., 2002). Knowledge and meaning therefore derive from situated, shared experience, interpreted through continual adaptation and improvisation (Markus et al., 2002, Middleton, 1998, Weick, 1998, Zack, 2000).

The core problem, in determining how people frame a specific situation, is that of making evidence of internal, cognitive framing structures visible, for analysis. Bruner (1990) use of storytelling as a way to elicit implicit perspectives is well-established (Boje, 1991, Gershon and Page, 2001, Mitroff and Kilmann, 1975). However, it must also be recognized that people invent or post-rationalize narratives, as a way of making sense of uncomfortable or inappropriate behavior and situations (Angus, 2001). Boland and Tenkasi (1995) suggest that narrative be combined with techniques to stimulate reflexivity (Schutz, 1967) and also suggest the use of cognitive maps (Axelrod, 1976, Eden et al., 1983) to elicit implicit reasoning. Most studies of situated framing employ a discourse analysis of interview data, observation, or technology interactions. Rommes (2002), in a “thinking aloud” study of Internet interactions, found that the way in which first-time users interpreted the city metaphor in their use of a digital city internet resource was very different to the way in which technical designers framed the ‘city’ metaphor. Jacobs (2001, 2002) employed discourse analysis and a co-term analysis of survey data, to compare framing constructs held by members of different professional groups. He concluded that the similar life-experience of members of specific groups led them to frame the role of information technology in similar ways. Prasad (1993) interviewed and observed members of diverse occupations, in a computerization project at a large health-services organization. He concluded that the way in which technology was interpreted resulted from sociocultural influences, such as membership of a specific professional group, combined with the ways in which their local managers and opinion-makers ascribed meaning to the technology. For example, managers who advocated use of the new information system by ascribing human qualities to it, such as smartness or knowledgeability, raised expectations of how the technology would behave that were widely adopted by those who worked for them and which were often at odds with their experience. From these studies, it can be seen that meaning and expectations are affected both by life-experience (derived through membership of a specific social or work-group) and also by interactions with other individuals who work in the same context.

Socially-Shared Cognition

Groups of people who regularly work together on shared tasks have been observed to develop a repertoire of shared frames. Shared frames provide cognitive “shortcuts” that permit a group to share common interpretations of the organization without the need for complex explanations (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995, Brown and Duguid, 1991, Fiol, 1994, Lave and Wenger, 1991). The development of a community of professional practice, such as a design group, is contingent on the development of shared (or intersubjectively acknowledged) meanings and language (Lave, 1991, Prus, 1991). The use of specific language reinforces the extent of shared understanding within a work-group and allows them to reconcile competing or complementary perspectives (Lanzara, 1983, Prus, 1991, Winograd and Flores, 1986). For example, IT developers share a vocabulary that is often unintelligible to other workers, but which allows them to communicate and coordinate work, using shorthand terms such as “this is a blue screen error”. IS design depends upon intersubjectivity for effective communication between team members to take place. Technical system designers, “successful in sharing plans and goals, create an environment in which efficient communication can occur” (Flor and Hutchins, 1991, page 54). This type of perspective-sharing requires not only shared knowledge, but also a shared system of sociocultural norms and values. Organizational framing is embedded within a local system of shared, socio-cultural values that make sense of “how we do things here” (Brown and Duguid, 1991, Lave and Wenger, 1991, MacLachlan and Reid, 1994).

“Knowledge and understanding (in both the cognitive and linguistic senses) do not result from formal operations on mental representations of an objectively existing world. Rather, they arise from the individual’s committed participation in mutually oriented patterns of behavior that are embedded in a socially shared background of concerns, actions, and beliefs.” (Winograd and Flores, 1986, page 78)

Orlikowski and Gash (1994) studied “technological frames”: those aspects of shared cognitive structures that relate to the assumptions, expectations and knowledge that people use to understand technology in organizations. By identifying various domains associated with shared framing perspectives, Orlikowski and Gash were able to identify differences between the technological frames held by technologists vs. those held by users of the technology. However, in their study, Orlikowski and Gash argued that members of two identifiable stakeholder groups (technologists and technology-users) possessed shared frames as they performed similar work, possessed similar backgrounds and worked within a cohesive organizational culture. This is not true in all cases: a general assumption that individual frames can be analyzed as representative of a specific interest group is highly dangerous. We cannot assume shared frames just because group members share a similar culture (Krauss and Fussell, 1991). We also cannot assume the existence of a shared culture among design group members: recently formed groups, or groups with new members have diverse systems of value, behavior and expectation (Lave and Wenger, 1991, Moreland et al., 1996).

An analysis of the degree of congruence[1] between different group frames may allow us to understand why negotiations between different groups, or decisions taken by representatives from specific organizational groups, result in a specific outcome, which may in turn help us to predict or to manage such outcomes. But defining shared content depends upon the way in which the framing concept is itself defined: we need to examine what is shared, to understand the degree of frame congruence (Cannon-Bowers and Salas, 2001). Cannon-Bowers and Salas (2001) suggest that what is shared in studies of shared cognition falls into four categories: (i) task-specific knowledge, relating to the specific, collective task in hand; (ii) task-related knowledge, experiential knowledge from similar tasks, of how to perform the work-processes that are required; (iii) knowledge of teammates, i.e. who knows what; and (iv) attitudes and beliefs that guide compatible interpretations of the environment. In the Orlikowski and Gash (1994) study, the assumption of shared frames refers only to congruence in the fourth category, attitudes and beliefs that guide compatible interpretations of the environment. Davidson (2002) extended the technological frames concept by analyzing the process of frame sharing and the dominance of different frame domains within a collaborative group over time. She discovered that the adoption of a specific, shared frame domain provided a conceptual boundary, or filter, to group discourse. Different frame domains became salient to the group at different points in the process, resulting in the adoption of a different strategy towards the IS design. Changes in the salient frame domain appeared to be triggered or accompanied by the adoption of a new group metaphor for the rationale behind the current design strategy. At times when the business value of IT frame-domain dominated group discourse, this led to a radical reconsideration of project requirements. At times when the IT delivery strategy frame-domain dominated group discourse, the group reverted to a more conservative definition of requirements, consistent with the perceived need to deliver a known product. This use of the term ‘frame domain’ thus relates to an intersection of the task-related, experiential-knowledge category and of the attitudes and beliefs category defined above (Cannon-Bowers and Salas, 2001).

So the development of shared frames may lead to more coherent group action and that the adoption of a new framing metaphor may reflect a shift in the dominant framing domain that triggers a change in group strategy. But to analyze shared frames, we must be satisfied that frame congruence exists within a group, before we can analyze congruence across different groups. To do this, we need to develop some nomothetic dimensions of the framing domain: a reduced set of dimensions that are generalizable to other contexts. There are few studies that examine shared framing in any detail and none were identified that examine all four of the categories of knowledge suggested by Cannon-Bowers and Salas (2001). Such studies are highly complex, requiring detailed analysis over multiple data samples.

Distributed Cognition

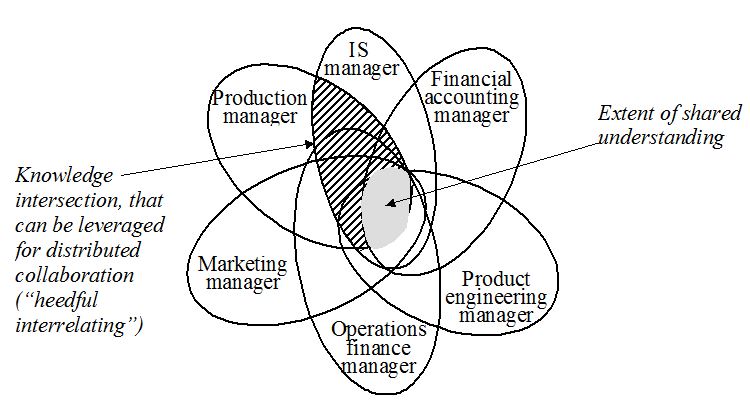

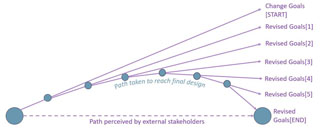

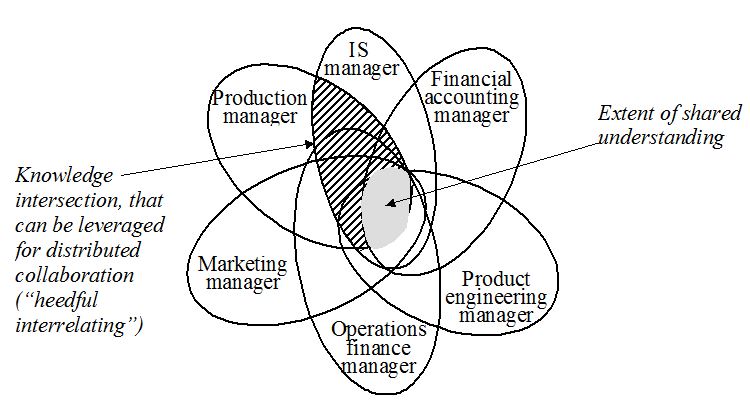

Star (1989) argues that the development of distributed systems should use a social metaphor, rather than a psychological one, where systems are tested for their ability to meet community goals. A social perspective requires the incorporation of differing viewpoints for decision-making. This accords with the position of many authors working on the problem of how to reflect the diversity of organizational needs in IS design (for example, Checkland, 1981, Checkland and Holwell, 1998, Eden, 1998, Eden et al., 1983, Weick, 1987, Weick, 2001). Weick (1987) discusses how teams performing collaborative tasks require a requisite variety of perspectives, to detect all of the significant environmental factors affecting collective decisions. But this is balanced by the need for a homogeneity of culture, within which team members can trust and interpret information from other team members. A wide spread of experience must be expected to cause problems of group cohesion and productivity (Krasner et al., 1987, Orlikowski and Gash, 1994). Thus, an IS design that spans multiple organizational groups or knowledge domains involves distributed cognition. Understanding within the design team is distributed: each individual can comprehend only a part of how the target system of human activities operates (Hutchins, 1991). The implications of distributed cognition are shown in Figure 1. The intersection of frames represents the degree of shared knowledge possessed by group members. This is relatively small when compared to the union, that represents the total knowledge of the group. A distributed cognition perspective assumes that “heedful interrelating” between members of a cooperative workgroup is required for effective collaboration (Weick and Roberts, 1993). Heedful interrelating is accomplished by mobilizing the shared understanding between individuals – the intersection between two segments of the diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Problem Of Distributed Cognition In Collaborative Work

Individual group members need to have some interdependency, or overlap, with other individuals in their framing of what needs to be done and why, to be able to coordinate action. But the distributed cognition perspective takes the position that there is a lack of overall congruence between how individuals frame organizational work. There is often an implicit model of a “collective mind” (Weick and Roberts, 1993) in much of the work on distributed cognition. But understanding is not so much shared between, as “stretched over” members of a cooperative group (Star, 1989). For example, a pilot may not understand how a navigational bearing was derived, but he shares sufficient knowledge-overlap with his navigator to be able to implement that bearing, as a change in direction. The concept of distributed cognition provides an alternative to the assumption of shared knowledge discussed above:

“ Distributed cognition is the process whereby individuals who act autonomously within a decision domain make interpretations of their situation and exchange them with others with whom they have interdependencies so that each may act with an understanding of their own situation and that of others.” (Boland et al., 1994, page 457).

So where does group knowledge reside? In operationalizing the concept of distributed knowledge, we note that interactions between individuals in collaborative work are mediated by “boundary objects” (Star, 1989). Boundary objects are physical artifacts, such as maps and diagrammatic models, that provide a representation of the superset of domain knowledge across various actors in cooperative work. Individuals are able to collaborate with others by ascribing a shared meaning to a boundary object. But boundary objects provide a sufficiently vague (global) representation of domain knowledge that they can be adapted to individual, local needs and constraints. For example, the topographical map of the New York subway system does not represent a detailed model of the locations and distances between stations. But it is sufficiently vague that it can be used to coordinate knowledge about what to do (“how do I get from here to there?”), ease of task (“do I have to change trains to get there?”), and travel costs (“which stations are in which travel zone?”). So it can coordinate collaboration between New York subway train drivers, platform guards, experienced travelers, tourists, ticket sales staff and ticket collectors, even when those individuals do not share the same knowledge about the elements that comprise the New York subway system. These physical representations or external products of human interaction often contain a shared understanding that is not possessed individually by the people who produced them (Hutchins, 1991, Star, 1989, Weick and Roberts, 1993). Thus, “shared” understanding is often not explicit, but communicated through representations of work and its context, that represent implicit and partial “maps” of what needs to be achieved (Hutchins, 1991, Norman, 1991, Schmidt, 1997, Star, 1989, 1998). If we examine external representations produced through collaborative work, we may be able to understand the sum of the group knowledge: the union of individual design-frames, as distinct from the intersections that represent shared frames. But we have to understand that these representations are also incomplete, as they have to be sufficiently vague to represent different things to different people. So the resulting knowledge is nomothetic (reduced and generalizable), rather than ideographic (specific to an individual knowledge-domain and context).

A distributed cognition perspective allows us to conceptualize a theory of design that permits agreement and negotiated outcomes while recognizing that each individual group member’s design understanding may be incomplete, emergent and not congruent with the understanding of others. Established workgroups develop an understanding of who knows what, that allows them to operate with heedfulness to others’ tasks and the division of collective work (Moreland et al., 1996). But local (domain-specific) knowledge is embedded in practice, rather than being capable of articulation (Fiol, 1994, Lave and Wenger, 1991). Members of a boundary-spanning design group may not realize that they hold distributed knowledge or differ over locally-defined framing perspectives and so may perceive misunderstandings as the consequence of political differences. For example, Gasson (1999) discussed how an IS design group that involved both technical developers and organizational psychologists interpreted their inability to cooperate as “personality problems”, yet this stemmed in a large part from the different framing filters that they imposed on the design problem. While the technical developers framed the design problem as experimenting with new technology to support user collaboration in constructing a knowledge-base, the psychologists framed the design problem as understanding how, where and why users would wish to collaborate and what role technology could play in this process. The two frame-domains were fundamentally incommensurate and the group lacked a mechanism for reconciling their different framing perspectives. In traditional work groups, there are experts on which the group may rely for guidance, whereas in workgroups where knowledge is distributed across work-related domains, perceptions of expertise are subjective and negotiated: there is a “symmetry of ignorance” (Rittel, 1972). This is borne out by a study of software development teams performed by Faraj and Sproull (2000) indicated that the effective management of distributed cognition is significant in ensuring team effectiveness. While the possession of expertise did not directly affect team performance, the coordination of expertise was seen as critical to team success. Social integration was considered more important than having an expert on the team (Faraj and Sproull, 2000). Thus, a shared understanding of who-knows-what is often more important to a collaborative design group than a shared understanding of the design itself.

The Analysis of Framing In Studies of Social Cognition

MacLachlan and Reid (1994) note that the studies of cognitive framing can take a static perspective, analyzing a “snapshot” of framing perspectives adopted by subjects around specific issues, or a dynamic analysis, where influences on the evolution of specific perspectives are assessed over time. The majority of research studies appear to conceptualize cognitive framing as static. Tan (1999, Tan and Hunter, 2002) and (Daniels et al., 2002) suggest that a repertory grid technique may be used for the assessment of individual framing perspectives. Several authors (e.g. Bougon and Komocar, 1990, Daniels and Johnson, 2002, Eden, 1998, Weick and Bougon, 1986) have used cognitive mapping (Axelrod, 1976), to elicit or compare causal models of individual and/or group belief-structures. (Orlikowski and Gash, 1994) coined the term “technological frames” to describe how individuals understand and interpret the role of technology in their work and organizational life. They used a qualitative analysis of themes in interview data to determine the extent of congruence between technological frames held by technology users vs. technology developers. These studies draw conclusions that avoid the question of how framing perspectives evolve through interaction with contextual phenomena and with other people, even over a short period of time (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995). In contrast, studies that investigate framing evolution require more complex methods and a longer duration. Urquhart (1999) used a discourse analysis of interview data, combined with videotapes of discussions between users and technical requirements analysts, to discover how their framing perspectives evolved through interaction. (Davidson, 2002) qualitatively analyzed both interview data and observational meeting data over a period of two and a half years, to understand differences between individual frames and the changing nature of the shared technological frames held by an IS development project group. Gasson (1998) used a combination of discourse analysis and Soft Systems Methodology, to elicit and analyze explicit and implicit frames, in an 18-month study of a group of managers engaged in the co-design of business and IT systems. Barr et al. (1992) constructed cognitive cause maps from 50 letters to shareholders published by two companies over a 25-year period, to understand how managers’ framing perspectives were affected by developments in their company environment.

When analyzing framing perspectives, it is important to understand two problems. The first is that we, as researchers are interpreting constructs that reside in the heads of others. Thus we encounter the intersubjectivity problem. Intersubjectivity requires a “leap of consciousness” (Schutz, 1967). This leap is developed further in Heidegger’s (1962) hermeneutic phenomenology, which takes the position that it is the interpretation of common experience that leads to an intersubjective understanding of another’s intention. As researchers, we are unlikely to possess such common experience unless we participate in those activities that form the subject of our subjects’ cognitive frames. It could be argued that it is only through “talking aloud” observation, participant observation or action research that we might understand the cognitive frames of our subjects. The second problem relates to the implicit nature of knowledge that resides “in the head”. Much of what we know is know-how, rather than know-what: skills-based or experiential knowledge that it is difficult or impossible for us to articulate (Garud, 1997, Lave and Wenger, 1991, Schön, 1983). We understand such knowledge through interactions with others and with the context in which we work (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995, Schön, 1983). It is often not possible to articulate such knowledge, either in a work situation, or in an interview situation. So eliciting framing perspectives is problematic, as subjects themselves may not be aware of them.

The identification of metaphors used in discourse may resolve these problems (Kendall and Kendall, 1993, Walsham, 1993). Metaphors play a central role in the analysis of organizational sensemaking, as they associate the properties of familiar concepts or subjects to a relatively unknown subject (Grant and Oswick, 1986). Just as Weick (Weick, 1979) discusses cognitive maps as a belief-structure through which we filter external evidence, Morgan (1986) argues that the use of metaphor implies a way of thinking and seeing that forms our understanding of the external world. So the use of common metaphors may imply the existence of a shared belief structure. For example, a group of American IS developers may use metaphors derived from Baseball, such as hitting a home run or covering first base (metaphors derived from Baseball), to indicate a shared pride or anxiety. British IS developers use metaphors derived from Cricket, such as hit for six or a sticky wicket, for the same purpose. But metaphors only present a part of the complex and dynamic cognitive constructs – referred to here as mental models or “frames” – that underlie individual and shared sensemaking (Klimoski and Mohammed, 1994, Oswick et al., 2002).

Metaphors represent an acknowledged similarity between one concept and another. We also need to develop ways of surfacing implicit knowledge, to understand fully how actors in a specific situation frame that situation. Some possible approaches are:

(a) Interpreting actor behavior in observational and action research studies;

(b) Using interactive methods that have been developed to surface implicit knowledge, such as Soft Systems Methodology (Checkland, 1981, Checkland and Holwell, 1998), the analysis of organizational “stories” (Gershon and Page, 2001, Mitroff and Kilmann, 1975), and cognitive mapping (Axelrod, 1976, Eden, 1998);

(c) Employing a qualitative approach that focuses on a hermeneutic and multi-faceted analysis of subjects’ discourse (Klimoski and Mohammed, 1994, MacLachlan and Reid, 1994, Oswick et al., 2002, Tannen, 1993). For example, a subject’s statement that they seek a document management tool might conflict with their expressed goal of tracking development activity-completion, indicating that they frame their problem as one of progress-management or worker-commitment, rather than framing the problem as related to the use of specific documents.

Employing the lens of socially-situated cognition allows us to examine the ways in which internal, human, knowledge structures shape how people interpret events in a particular way, or sensitize them to specific events and phenomena over others (MacLachlan and Reid, 1994, Winograd and Flores, 1986). An IS design can be seen as the result of negotiation between multiple, socially-situated “worlds”, that represent reality in different ways to different people. The resulting IS reflects intersections between an overlapping set of individual and group perspectives, that shift and evolve as the design proceeds. Problem contents and boundaries are subjective, multiple and competing: “relevant” organizational problems are determined through argumentation and negotiation (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995, Rittel, 1972). Taking a framing perspective to socially-situated cognition allows us to conceptualize how similarities and differences in individual perspectives and understandings guide collective action.

A Framework For Social Cognition in Information Systems

To operationalize these levels of analysis, it is necessary to understand the different foci of different types of analysis and the assumptions underlying these foci. The dominant perspectives of socially-situated cognition, for each of the three theoretical lenses discussed above, are summarized in Table 1, through a discussion of how each perspective operationalizes the “framing” concept in different ways.

Table 1. A Framework Of Analytical Perspectives On Socially-Situated Cognition in IS

| Level |

Nature of Concept |

Focus and Assumptions |

Exemplars |

| Socially-Situated Cognition |

Static framing: a snapshot of idiographic (locally-specific) framing perspectives adopted by individuals. |

Defines individual frame domains and content to understand differences between individuals. Assumes that snapshot represents ongoing framing perspectives. |

(Tan, 1999)

(Rommes, 2002)

(Jacobs, 2002) |

|

Dynamic framing: a comparative analysis of framing perspectives over time. |

Analyzes changes in, and/or influences on individual frame domains and content. |

(Urquhart, 1999)

(King, 1997) |

| Socially-shared Cognition |

Static frame comparison: a nomothetic (generalizable) analysis of shared framing perspectives in an interest group, or between groups. |

Analyzes congruence in frame domains and content across members of a specific group, or assumes congruence within group, to analyze congruence between groups. Assumes that a snapshot represents beliefs, attitudes and knowledge generally held by subjects. Also assumes that frames can be reduced to a few, nomothetic concepts. |

(Orlikowski and Gash, 1994)

(Sahay et al., 1994)

(Barrett, 1999)

(Gallivan, 2001) |

|

Dynamic frame comparison: a comparative analysis of collective frames over time. |

Assumes frame congruence between members of work or interest group, to analyze changes in dominant or shared frames over time. |

(Davidson, 2002)

(Gasson, 1998)

(McLoughlin et al., 2000) |

| Distributed Cognition |

Static comparison of frame congruence and differences: an analysis of ways in which work is coordinated across different knowledge or work domains. |

Focuses on locally-constructed nature of knowledge and belief structures. Therefore, this type of analysis tends to privilege ideographic (specific) aspects of framing over nomothetic (generalizable) aspects. |

(Ciborra and Andreu, 2000)

(Orlikowski, 2002)

(Carlile, 2002) |

|

Dynamic analysis of frame intersections and union: an analysis of interactions that permit “heedful interrelating” between collaborative group members. |

Analyzes distributed group work through the analogy of a “collective” mind. Examines coordination of diverse framing perspectives, usually privileging nomothetic aspects. |

(Weick and Roberts, 1993)

(Gasson, 2004)

(Hutchins and Klausen, 1998) |

|

Transactive frame mediation: an analysis of how an external (technology-mediated) group “memory” or “knowledge base” may be constructed and used. |

Analyzes mediated “workspaces” or boundary-objects as a resource for distributed knowledge management in collaborative work. Assumes that collective, or coordinating knowledge may be represented in external artifacts. |

(Star, 1989)

(Zhang and Norman, 1994)

(Perry et al., 1999)

(Suchman, 1998)

(Hollan et al., 2002) |

Conclusion: Application Of The Framework

The literature review and the framework presented above summarized different analytical perspectives on the analysis of socially-situated cognition, by operationalizing the different approaches to “frame” analysis that are found in the IS and related literatures. It can be seen that the focus and underlying assumptions of each approach are very different. Each approach is intended to achieve a different end and so each suffers from the limitations of its specific set of assumptions about the nature of the data, or the ways in which it can be analyzed. This is not to suggest that such analyzes are valueless. But the different perspectives on socially-situated cognition that are represented here are often conflated. This leads to muddled analyses of “technological frames” (or a similar construct), with no clear objective or analytical model underlying the production of research evidence.

The framework presented here may help to clarify the selection of a specific approach to the analysis of socially-situated cognition. Specifically, it differentiates between different modes of knowing, that require different methods of investigation. The study of cognitive frames is a relatively recent departure for IS researchers and many concepts from the psychology and organizational literatures have become conflated in the process of translation. This framework identifies three aspects of social cognition, that are relevant to the current state of IS research:

- Socially-situated cognition, which relates to an individual perspective, that is situated in a socio-technical context;

- Socially-shared cognition, which relates to a group perspective, that filters and guides shared interpretations of collective goals, contextual events and other phenomena;

- Distributed cognition, which relates to a “shared memory” or group consciousness, that is not possessed in common, but stretched across members of a collaborative group.

Each of these aspects of framing in social cognition may be analyzed as a static construct, taking a “snapshot” of individual or group frames to understand differences or congruence between various perspectives, or a dynamic construct, tracing the evolution of framing perspectives over time. Additionally, the distributed cognition aspect of framing also has associated with it a transactive memory construct, that investigates the ways in which technology might mediate group knowledge resources to support collaborative work.

Of course, the perspectives presented above are not mutually exclusive. But it is important to have a clear notion of what each analytical perspective achieves and to understand its limitations. The framework presented here depicts the different aspects of individual, group and inter-group frames dealt with by each analytical perspective. It is hoped that this will provide a mechanism to make the analysis of — and explanations from — studies of social cognition more open, explicit and rigorous.

References

Angus, J. (2001) To Tell the Truth. Knowledge Management Magazine, May.

Axelrod, R. (1976) The cognitive mapping approach to decision making. In Structure of Decision (Ed, Axelrod, R.) Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 221-250.

Barr, P. S., Stimpert, J. L. and Huff, A. S. (1992) Cognitive Change, Strategic Action, and Organizational Renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 13 15-36.

Barrett, M. I. (1999) Challenges of EDI adoption for electronic trading in the London Insurance Market. European Journal of Information Systems, 8 (1), 1-15.

Bartlett, F. (1932) Remembering: A Study In Experimental And Social Psychology, Cambridge University Press, London, UK.

Berger, P. L. and Luckman, T. (1966) The Social Construction Of Reality: A Treatise In The Sociology of Knowledge, Doubleday & Company Inc., Garden City N.Y.

Boje, D. M. (1991) The Storytelling Organization: A Study of Story Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36 (1), 106-126.

Boland, R., J and Tenkasi, R., V, (1995) Perspective Making and Perspective Taking in Communities of Knowing. Organization Science, 6 (4), 350-372.

Boland, R. J., Tenkasi, R., V and Te’eni, D. (1994) Designing Information Technology to Support Distributed Cognition. Organization Science, 5 (3), 456-475.

Bougon, M. G. and Komocar, J. M. (1990) Directing Strategic Change: A Dynamic Wholistic Approach,. In Mapping Strategic Thought (Ed, Huff, A. S.) Wiley and Sons, pp. 135-163.

Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (1991) Organizational Learning and Communities of Practice: Toward a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation. Organization Science, 2 (1), 40-57.

Bruner, J. (1990) Acts of Meaning, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Cannon-Bowers, J. A. and Salas, E. (2001) Reflections on shared cognition. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22 195-202.

Carlile, P. R. (2002) A Pragmatic View of Knowledge and Boundaries. Organization Science, 13 (4), 442-455.

Checkland, P. (1981) Systems Thinking Systems Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester UK.

Checkland, P. and Holwell, S. (1998) Information, Systems and Information Systems: Making Sense of the Field, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester UK.

Ciborra, C. U. and Andreu, R. (2000) “Knowledge Across Boundaries: Managing Knowledge In Distributed Organizations,” Working Paper #93, London School of Economics, ISSN 1472-9601.

Daniels, K. and Johnson, G. (2002) On trees and triviality traps: Locating the debate on the contribution of cognitive mapping to organizational research. Organization Studies, 23 (1), 73-81.

Daniels, K., Johnson, G. and Chernatony, L. d. (2002) Task and institutional influences on managers’ mental models of competition. Organization Studies, 23 (1), 31-62.

Davidson, E. J. (2002) Technology Frames and Framing: A Socio-Cognitive Investigation of Requirements Determination. MIS Quarterly, 26 (4), 329-358.

Eden, C. (1998) Cognitive mapping. European Journal of Operational Research, 36 1-13.

Eden, C., Jones, S. and Sims, D. (1983) Messing About In Problems, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Ensink, T. and Sauer, C. (2003) Introduction. In Framing And Perspectivising In Discourse (Eds, Ensink, T. and Sauer, C.) University of Groningen, Germany.

Eysenck, M. W. and Keane, M. T. (1990) Cognitive Psychology, Erlbaum Press, Hove, East Sussex UK.

Faraj, S. and Sproull, L. (2000) Coordinating Expertise in Software Development Teams. Management Science, 46 (12), 1554-1568.

Fiol, C. M. (1994) Consensus, Diversity and Learning In Organizations. Organization Science, 5 (3), 403-420.

Flor, N. V. and Hutchins, E. L. (1991) Analyzing distributed cognition in software teams: a case study of team programming during perfective software maintenance. Proceedings of the Empirical Studies of Programmers – Fourth Workshop Norwood NJ: Ablex, 36-59.

Fodor, J. (1975) The Language of Thought., Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Gallivan, M. J. (2001) Meaning to change: How diverse stakeholders interpret organizational communication about change initiatives. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44 (4), 243-266.

Garud, R. (1997) On the distinction between know-how, know-why and know-what in technological systems. In Advances In Strategic Management, Vol. 14 (Eds, Huff, A. S. and Walsh, J. P.) JAI Press Inc., Greenwich, Connecticut, pp. 81-101.

Gasson, S. (1998) Framing Design: A Social Process View of Information System Development. Proceedings of the Proceedings of The Nineteenth International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 98), Helsinki Finland,

Gasson, S. (1999) The Reality of User-Centered Design. Journal of End User Computing, 11 (4), 3-13.

Gasson, S. (2004) The Management of Distributed Organizational Knowledge. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences (HICSS-37), Manua, Hawaii,

Gentner, D. and Stevens, A. L. (1983) Mental Models, Erlbaum, Hillsdale N.J.

Gershon, N. and Page, W. (2001) What storytelling can do for information visualization. Communications of the ACM, 44 (3), 31-37.

Goffman, E. (1974) Frame Analysis, Harper and Row, New York, NY.

Grant, D. and Oswick, C. (1986) Introduction: Getting the Measure of Metaphors. In Metaphor and Organizations (Ed, Grant, D. a. O., C.) Sage, London.

Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and Time, Harper & Row New York, New York NY.

Hollan, J., Hutchins, E. and Kirsh, D. (2002) Distributed cognition: toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 7 (2), 174 – 196.

Hutchins, E. (1991) The Social Organization of Distributed Cognition. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, Vol. pp. 283-307. (Eds, Resnick, L. B., Levine, J. M. and Teasley, S. D.) American Psychological Association., Washington DC.

Hutchins, E. and Klausen, T. (1998) Distributed cognition in an airline cockpit. In Cognition and Communication at Work (Eds, Engestrom, Y. and Middleton, D.) Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 15-34.

Jacobs, N. (2001) Information technology and interests in scholarly communication: a discourse analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52 (13), 1122 – 1133.

Jacobs, N. (2002) Co-term network analysis as a means of describing the information landscapes of knowledge communities across sectors. Journal of Documentation, 58 (5), 548-562.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983) Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Kelly, G. A. (1955) The Psychology Of Personal Constructs., W.W. Norton & Company Inc., New York, NY.

Kendall, J. E. and Kendall, K. E. (1993) Metaphors and methodologies: Living beyond the systems machine. MIS Quarterly, 17 (2), 149-171.

King, S. (1997) Tool support for systems emergence: A multimedia CASE tool. Information and Software Technology, 39 (5), 323-330.

Klimoski, R. and Mohammed, S. (1994) Team Mental Model: Construct Or Metaphor? Journal of Management, 20 (2), 403-437.

Krasner, H., Curtis, B. and Iscoe, N. (1987) Communication breakdowns and boundary spanning activities on large software projects. In Empirical Studies of Programmers: Second Workshop, Vol. pp 65-82 (Eds, Olson, G. M., Sheppard, S. and Soloway, E.) Ablex, New Jersey.

Krauss, R. M. and Fussell, S. R. (1991) Constructing shared communicative environments. In Perspectives on socially shared cognition (Eds, Resnick, L. B., Levine, J. M. and Teasley, S. D.) American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 172-200.

Lanzara, G. F. (1983) The Design Process: Frames Metaphors And Games. In Systems Design For With and By The Users (Eds, Briefs, U., Ciborra, C. and Schneider, L.) North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

Lave, J. (1991) Situating Learning In Communities of Practice. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, Vol. pp 63-82 (Eds, Resnick, L. B., Levine, J. M. and Teasley, S. D.) American Psychological Association, Washington DC.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK.

MacLachlan, G. and Reid, I. (1994) Framing and Interpretation, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

Majchrzak, A., Rice, R. E., Malhotra, A., King, N. and Ba, S. (2000) Technology Adaptation: The Case of a Computer-Supported Inter-Organizational Virtual Team. MIS Quarterly, 24 (4), 569-600.

Markus, M. L., Majchrzak, A. and Gasser, L. (2002) A Design Theory For Systems That Support Emergent Knowledge Processes. MIS Quarterly, 26 (3), 179-212.

McLoughlin, I., Badham, R. and Couchman, P. (2000) Rethinking political process in technological change: Socio-technical configurations and frames. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 12 (1), 17-37.

Middleton, D. (1998) Talking work: Argument, common knowledge and improvisation in teamwork. In Cognition and Communication at Work (Eds, Engestrom, Y. and Middleton, D.) Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 233-256.

Minsky, M. (1975) A Framework For Representing Knowledge. In The Psychology of Computer Vision (Ed, Winston, P.) McGraw Hill, New York, pp. 211-277.

Mitroff, I. I. and Kilmann, R. H. (1975) Stories Managers Tell: A New Tool For Organisational Problem Solving. Management Review, 64 (7), 18-28.

Moreland, R. L., Argote, L. and Krishnan, R. (1996) Socially shared cognition at work: Transactive memory and group performance. In What’s Social About Social Cognition? Research on Socially Shared Cognition in Small Groups (Eds, Nye, J. and Brower, A.) Sage, Thousand Oaks CA.

Morgan, G. (1986) Images of Organization, Sage, Newbury Park CA.

Neisser, U. (1976) Cognition and Reality, W.H. Freeman, San Francisco CA.

Norman, D. A. (1991) Cognitive Artifacts. In Designing Interaction: Psychology At The Human-Computer Interface (Ed, Carroll, J. M.) Cambridge University Press, UK.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2002) Knowing in Practice: Enabling a Collective Capability in Distributed Organizing. Organization Science, 13 (3), 249-273.

Orlikowski, W. J. and Gash, D. C. (1994) Technological Frames: Making Sense of Information Technology in Organizations. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 12 (2), 174-207.

Orlikowski, W. J. and Hofman, D. (1997) An Improvisational Model of Change Management: The Case of Groupware Technologies. Sloan Management Review, 38 (2), 11-22.

Orlikowski, W. J., Yates, J., Okamura, K. and Fujimoto, M. (1995) Shaping Electronic Communication – the Metastructuring of Technology in the Context of Use. Organization Science, 6 (4), 423-444.

Oswick, C., Keenoy, T. and Grant, D. (2002) Metaphor And Analogical Reasoning In Organization Theory: Beyond Orthodoxy. Academy of Management Review, 27 (2), 294-303.

Perry, M., Fruchter, R. and Rosenberg, D. (1999) Co-ordinating distributed knowledge: an investigation into the use of an organisational memory. Cognition, Technology and Work, 1 142-152.

Porac, J. M., J. and Stubbart, C. (1996) Introduction. In Cognition within and betwen organizations (Eds, Meindl, J., Stubbart, C. and Porac, J.) Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. ix-xxiii.

Prasad, P. (1993) Symbolic processes in the implementation of technological change: A symbolic interactionist study of work computerization. Academy of Management Journal, 36 (6), 1400-1429.

Prus, R. C. (1991) Symbolic interaction and ethnographic research : intersubjectivity and the study of human lived experience, State University of New York Press, Albany.

Resnick, L. B. (1991) Shared Cognition: Thinking As Social Practice. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition (Eds, Resnick, L. B., Levine, J. M. and Teasley, S. D.) American Psychological Association, Washington DC, pp. 1-20.

Rittel, H. W. J. (1972) “Second Generation Design Methods,” Reprinted in N. Cross (ed.), Developments in Design Methodology, J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 1984, pp. 317-327., Interview in: Design Methods Group 5th Anniversary Report,

Rommes, E. (2002) Worlds apart: Exclusion-processes in DDS. Proceedings of the Digital Cities 2: Computational and Sociological Approaches, Second Kyoto Workshop on Digital Cities, Kyoto, Japan, 219-232.

Sahay, S., Palit, M. and Robey, D. (1994) A relativist approach to studying the social construction of information technology. European Journal of Information Systems, 3 (4), 248-258.

Schank, R. C. and Abelson, R. P. (1977) Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding: An inquiry into human knowledge structures, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ.

Schmidt, K. (1997) Of Maps and Scripts. Proceedings of the Proceedings of GROUP 97 ACM SIG: Distributed Group Work, University of Phoenix Arizona, 138-147.

Schön, D. A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action, Basic Books, New York NY.

Schutz, A. (1967) The phenomenology of the social world, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, IL.

Star, S. L. (1989) The Structure of Ill-Structured Solutions: Boundary Objects and Heterogeneous Distributed Problem Solving. In Distributed Artificial Intelligence, Vol. II. (Eds, Gasser, L. and Huhns, M. N.) Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., San Mateo CA, pp. pp. 37-54.

Star, S. L. (1998) Working together: Symbolic interactionism, activity theory and distributed artificial intelligence. In Cognition and Communication at Work (Eds, Engestrom, Y. and Middleton, D.) Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 296-318.

Strauss, A. L. (1978) A Social World Perspective. In Studies In Symbolic Interaction, Vol. 1 (Ed, Denzin, N. K.) Jai Press Inc., Greenwich, Connecticut, pp. 119-128.

Strauss, A. L. (1983) Continual Permutations of Action, Aldine de Gruyter, New York.

Suchman, L. (1987) Plans And Situated Action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge MA.

Suchman, L. (1993) Response to Vera and Simons Situated Action: A Symbolic Interpretation. Cognitive Science, 17 (1), 71-76.

Suchman, L. (1998) Constituting shared workspaces. In Cognition and Communication at Work (Eds, Engestrom, Y. and Middleton, D.) Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 350.

Tan, F. B. (1999) Exploring Business-IT Alignment Using the Repertory Grid. Proceedings of the 10th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Wellington, New Zealand, 931-943.

Tan, F. B. and Hunter, M. G. (2002) The Repertory Grid Technique: A Method For The Study of Cognition In Organizations. MIS Quarterly, 26 (1), 39-57.

Tannen, D. (1993) What’s In A Frame? In Framing in Discourse (Ed, Tannen, D.) Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Urquhart, C. (1999) Themes in early requirements gathering: The case of the analyst the client and the student assistance scheme. Information Technology and People, 12 (1), 44-70.

Vickers, G. (1974) some of which is reprinted in Checkland, P. (1985) “From Optimizing To Learning: A Development of Systems Thinking For The 1990s”, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 36 (9), pp. 757-767.

Vitalari, N. P. and Dickson, G. W. (1983) Problem-Solving for Effective Systems Analysis: An Experimental Exploration. Communications of the ACM, 26 (11), 252-260.

Walsham, G. (1993) Reading the organization: metaphors in information management. Journal of Information Systems, 3 (33-46).

Weick, K. E. (1979) The Social Psychology of Organizing, Addison-Wesley, Reading MA.

Weick, K. E. (1987) Organizational Culture As A Source Of High Reliability. California Management Review, 29 (2), 112-127.

Weick, K. E. (1998) Improvisation as a Mindset for Organizational Analysis. Organization Science, 9 (5), 543-555.

Weick, K. E. (2001) Making Sense of the Organization, Blackwell Scientific, Malden MA.

Weick, K. E. and Bougon, M. (1986) Organizations as cognitive maps: Charting ways to success and failure. In The Thinking Organization (Eds, H. P. Sims, J., Gioia, D. A. and Associates) Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 102-135.

Weick, K. E. and Roberts, K. H. (1993) Collective Mind In Organizations: Heedful Interrelating on Flight Decks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38.

Winograd, T. and Flores, F. (1986) Understanding Computers And Cognition, Ablex Corporation, Norwood New Jersey.

Zack, M. H. (2000) Jazz improvisation and organizing: Once more from the top. Organization Science, 11 (2), 227-234.

Zhang, J. and Norman, D. A. (1994) Representations in Distributed Cognitive Tasks. Cognitive Science, 18 (87-122).

Notes:

[1] Frame congruence does not imply that frames are identical, but that they are related in structure (possessing common categories of frames) and content (with similar values in the common categories) Orlikowski, W. J. and Gash, D. C. (1994) Technological Frames: Making Sense of Information Technology in Organizations. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 12 (2), 174-207..