Human-Centered Design

In the last few years, the terms human-centered and user-centered have become synonymous in HCI and IT design, with a focus on disciplines such as “user experience” and “interaction design.” Here I will argue that neither discipline really deals with the core issues of human-centered design.

Human-centeredness in design involves designing technology artifacts, applications, and platforms that provide a “support system” to people performing specific work or play activities as individuals, or collaborating around a set of (more or less) well-defined aims – often messily and exploratively. Asking people to describe their requirements for technology to support them in their activity doesn’t work because no-body really stops top think about how they work, or what they do to achieve a goal. When they are forced to do so, they will describe how work should be done – the formal system of procedures and rules – rather than how it is done – the informal, socially-situated system that makes work activities fit with their environment and the objectives that people have.

People are seldom alone in what they do, even when engaging in individual activity. They socialize with other people and exchange ideas, they seek advice on how to proceed, and they collaborate to achieve shared – or similar – goals. When confronted with a novel problem, most people turn to a “small world” network of trusted social contacts for input – people who share their values and perspectives – rather than conducting a wider search that includes subject experts and knowledge resources (Chatman, 1991). Even when working alone, we are never truly alone. We are thrown into a working environment that existed before we joined – a self-contained world of work and social activity that we can only understand through participation (Weick, 2004). Professionalism and practice in one organization are completely different to the practices and standards applied in another.

When we try to understand the “user” of a software application or system, we often fail miserably because we only see the formal work activities that they perform. We miss the web of activities that their formal activity is a part of – the multiple other human-activity systems they interact with, to get things done. User-experience design is reductionist in its focus on interaction design. It takes a human being, rich in purpose and understanding, and reduces them to the role of artifact user. Not only that, but by implication, the user of a pre-defined artifact, whose purpose is understood, but whose mechanisms of interaction remain to be fully defined. By focusing on conceptual models of use, user scripts, and activity/task frameworks for work-analysis e.g. Sharp, Preece, and Rogers (2019), it isolates the user from the social context of work, describing activities in terms of fixed procedures and embedding assumptions about how and why the artifact will be used. It loses the joyful multivocality of the human-centered approach to design. Instead of understanding that thrownness is a temporary state, where there is a choice between reaction or being proactive, user-centered design embeds reaction as a paradigm. It separates tasks from workflows, making each interaction an end in itself and enforcing the approach to design that led Lucy Suchman to write her famous treatise on situated design (Suchman, 1987, 2007). There is no linked flow of work processes, where the human being knows that (for example) they have already photocopied the report covers (onto special cardstock) and the early chapters, so now have only to copy later chapters. There is the dumb lack-of-saved-status machine, which jams halfway, then asks the user to reload the report pages in their original order, starting with the covers which need the user to load special cardstock into the paper feeder. Which they already did.

We can support this world by understanding the various purposes of human activity and designing technology to assist in those purposes (Checkland and Winter, 2000). Human-centered design differs from user-centeredness by being systemic and multi-vocal: it is aware of the multiple networks of activity in which a human technology user engages, simultaneously. Unlike user-centered design, which focuses on a single, definable work-goal, human-centered design appreciates the multiple goals that people pursue simultaneously, for different purposes. Human-centered design appreciates the social and organizational context of work, employing analytical approaches and methods that explore the complexity of the activities that we do – and the social networks we inhabit to do them.

Designing for humans rather than users is a choice:

- Human-centered design explores the multiple, purposeful systems of human-activity that are required to achieve even simple work (or play) goals.

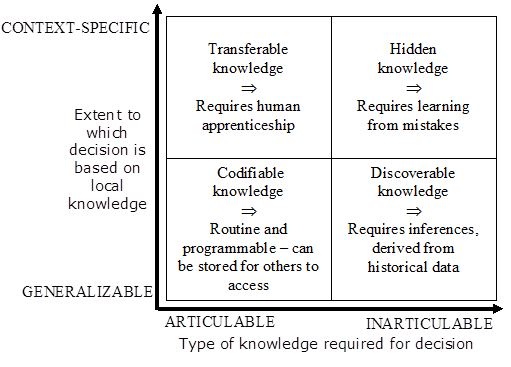

- It treats the participants in a human activity system as autonomous individuals, not agents to be modeled, controlled, and curtailed. Human-centered design respects and supports the local knowledge required to act skillfully, using local knowledge and various forms of tacit or implicit knowledge to perform work that is often not recognized as knowledge work.

- It recognizes that a social system of information exchange exists, of which the designed technology artifact or software is only a part, and that humans need to exercise a deliberative choice about what to record and why. Any computer-based system of data is part of a wider, human-network-based system of information.

- Because it appreciates work as part of a wider social system, human-centered design involves a conscious decision to support the informal communications and activities that keep the system of work connected and informed – for example, water-cooler conversations or phone calls. These informal channels produce more knowledgeable participants in the system of work, rather than resulting in recorded data records or written resources. They are often omitted from – or worse, designed out of – the formal system of “user experience design.”

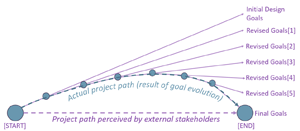

- Above all, it acknowledges that knowledge, understanding, and the meanings that we ascribe to work are emergent. We understand how to do things by doing them, then reflecting on what we did and how – after which we have a better understanding of how to do them next time. Designing any particular set of procedures into a computer-based system is not only a waste of time, but may be counterproductive, as we constantly improvise and improve on how we did things previously (learning-by-doing). Human-centered systems design allows the human to be in control of their work, rather than the IT system.

So no – “user experience design” and “interaction design” do not support human-centeredness in work (or play). They seek to humanize the artificial processes imposed by transaction-based systems by associating these with perspectives that acknowledge the psychology of human activity, learning, and interactions with technology. But they don’t even scratch the surface of understanding situated, systemic activity. For that, you need to employ methods that complicate your perspective, such as Soft Systems Analysis (Checkland, 2000; Checkland and Poulter, 2006) – and to take human-centeredness seriously.

To conclude, user-centered design – as the term is employed in HCI and UX – is not the same as human-centered design. User-centered design is aimed at mitigating and improving the experience of using a system of technology that was designed for another purpose than those the user prioritizes – to make money, to “engage” users on the website so they return (and spend more money), and to publicize the firm’s products and services. In contrast, human-centered design is an approach that starts with user values, priorities, and purposes. It seeks to afford uses of the system that fulfill how the user would like to access the features that they value and expect. It designs the flow of use-interactions around the expected user flow of work (or play), allowing the user to configure this flow how they want. It does not make you do illogical or stupid things, like reloading all the sheets in a photocopier feed in their original order, even when the copy failed on the last-page-but one. It does not make you enter the same information repeatedly, because the designer was too unimaginative to anticipate that a user might want to change some of the options they had selected earlier (e.g. when booking an airline ticket). And it doesn’t make you go through seven layers of a menu to reach the one page you need.

Human-centered design is performed by people who talk to users, learn to think like users, and walk alongside them in their work. These designers not only prototype and evaluate their designs, but also listen to the feedback they are given. They value user input and see it an critical to their portfolio of design experience. In the design literature of the 1980s there was a lot of discussion of how user representatives would “go native,” when participating in design projects, learning to think like designers and subsuming the interests of their fellow users in the process. In the 2020s, we need to see more IT designers going native, learning to think like users, reworking IT system designs to support how users work, and valuing the aspects of system design that users value. That is human-centered design.

References

Chatman, E.A. 1991 “Life in a Small World: Applicability of Gratification Theory to Information-Seeking Behavior,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science (42:6), pp. 438–449.

Checkland, P. 2000 “Soft systems methodology: a thirty year retrospective,” Systems Research and Behavioral Science (17), pp. S11-S58.

Checkland, P., and Poulter, J. 2006. Learning For Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology, and its use Practitioners, Teachers and Students Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2006.

Checkland, P., and Winter, M.C. 2000 “The relevance of soft systems thinking,” Human Resource Development International (3:3), pp. 411-417.

Sharp, H., Preece, J., and Rogers, Y. 2019. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction, 5th EditionWiley, UK, 2019.

Suchman, L. 1987. Plans And Situated Action Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Suchman, L. 2007. Human–machine reconfigurations: Plans and situated actions Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Weick, K.E. 2004. “Designing For Throwness,” in: Managing as Designing, R. Boland, J and F. Collopy (eds.), Stanford CA: Stanford Uniersity Press, pp. 74-78.

Selected Papers:

Gasson, S. (2008) ‘A Framework For The Co-Design of Business and IT Systems,’ Proceedings of Hawaii Intl. Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-41), 7-10 Jan. 2008. Knowledge Management for Creativity and Innovation minitrack, p348. http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/HICSS.2008.20.

Gasson, S. (2005) ‘Boundary-Spanning Knowledge-Sharing In E-Collaboration’ in Proceedings of Hawaii Intl. Conf. on System Sciences (HICSS-38), Jan. 2005. http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/HICSS.2005.123

Gasson, S. (2003) ‘Human-Centered vs. User-Centered Approaches To Information System Design‘, Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application (JITTA), 5 (2), pp. 29-46.

Gasson, S. (1999) ‘A Social Action Model of Information Systems Design’, The Data Base For Advances In Information Systems, 30 (2), pp. 82-97.

Gasson, S. (1999) ‘The Reality of User-Centered Design‘, Journal of End User Computing, 11 (4), pp. 3-13.